Zanne Domoney-Lyttle reviews Sarah Lightman’s graphic novel The Book of Sarah.

Sarah Lightman’s The Book of Sarah is an ambitious and moving text-image chronicle of her experiences from childhood to parenthood, embedded within a framework of Jewish feminist approaches. It is a biography intertwined with a hazy memory, family mythology, and some meaningful and other not-so meaningful objects which combine in a forceful way to remind the reader that our own life stories are a mixture of fact and fiction. As comic writer Grant Morrison once noted, we live in the stories we tell ourselves, and Lightman’s book is a textual and visual reminder of that. As Lightman puts it: ‘dynamics and tensions are ossified in stories repeated through the years, traditional retellings at family meals and in front of new friends’. This layering of remembered and retold personal narratives come to shape our identities in ways Lightman attempts to untangle and contextualise in her work.

The story is told through a series of images of often mundane objects or unidentifiable buildings complemented by text. It must be noted at the outset that the artwork is a triumph; it has always been this reader’s personal preference to see the hand of the artist at work in the art, and Lightman’s art is full of her touch. The artwork is mixed media; sometimes simple sketches, other times elaborately detailed pen and pencil work, and there are also paintings and perhaps other media in use. A strong example of Lightman’s abilities and wide range of media can be seen in a double-page spread of various artist self-portraits. One could spend a long time looking at each panel to gauge the emotion and expression of each face, though all share a kind of sadness or tiredness between them. Mostly, the artwork is almost tactile, inviting the reader to touch the pages, to feel for the textures which cannot be reproduced in prints but which are evidently there in the indentations of the pencil marks, the thickness of the paint (see for example the front cover image), and the areas where fingerprints and eraser marks are faintly visible. Such a style complements the narrative of the book because it humanises the subject and encourages the reader to appreciate the life of the creator behind the book’s content.

Clearly invoking the Hebrew Bible as a reference point, the title The Book of Sarah is a slightly amusing yet important play on biblical books which name their central characters (e.g. The Book of Ruth, The Book of Job, etc.). Lightman describes in what may be considered the preface to the book, that while both her siblings shared a name with a biblical book and figure (Esther and Daniel), the figure of Sarah (with whom she shares a name) is similarly central to Jewish narratives of genealogy and covenant but is not granted such a privilege. Lightman’s Book of Sarah is then a nod to the biblical matriarch and the importance of her position in Jewish history and tradition, as well as an account of Lightman’s biography. The two are intertwined at points given that the stories of both the biblical Sarah and Lightman share themes of mental health, family, genealogy, fertility and motherhood.

The book is divided into chapters which all reference biblical literature: ‘Genesis,’ ‘Exodus,’ ‘Bamidbar,’ ‘Numbers,’ ‘Leviticus,’ ‘Harry’s Genesis,’ ‘Revelations,’ and ‘Apocrypha.’ ‘Genesis’ tells of Lightman’s beginnings, her family, her home, and her early education in London. ‘Exodus’ recounts Lightman’s move from England to New York, time spent in Italy, and a return to England. In this chapter, the emotional complexity of the artwork comes to the fore. For example, a frantic sketch of a door representing the possibilities that extend beyond its frame is positioned opposite a neat, controlled drawing of a house signifying potential boundaries and restrictions were Lightman to have taken an alternative path. Visual details such as these draw the reader into Lightman’s experience, rather than the words. ‘Badmidbar’ charts Lightman’s return from New York and her continued questions and musings on her situation, but the real success of the book lies in the latter chapters, and especially in ‘Leviticus,’ which juxtaposes the death of Lightman’s grandfather with her newly married status and her thoughts of future possibilities such as pregnancy.

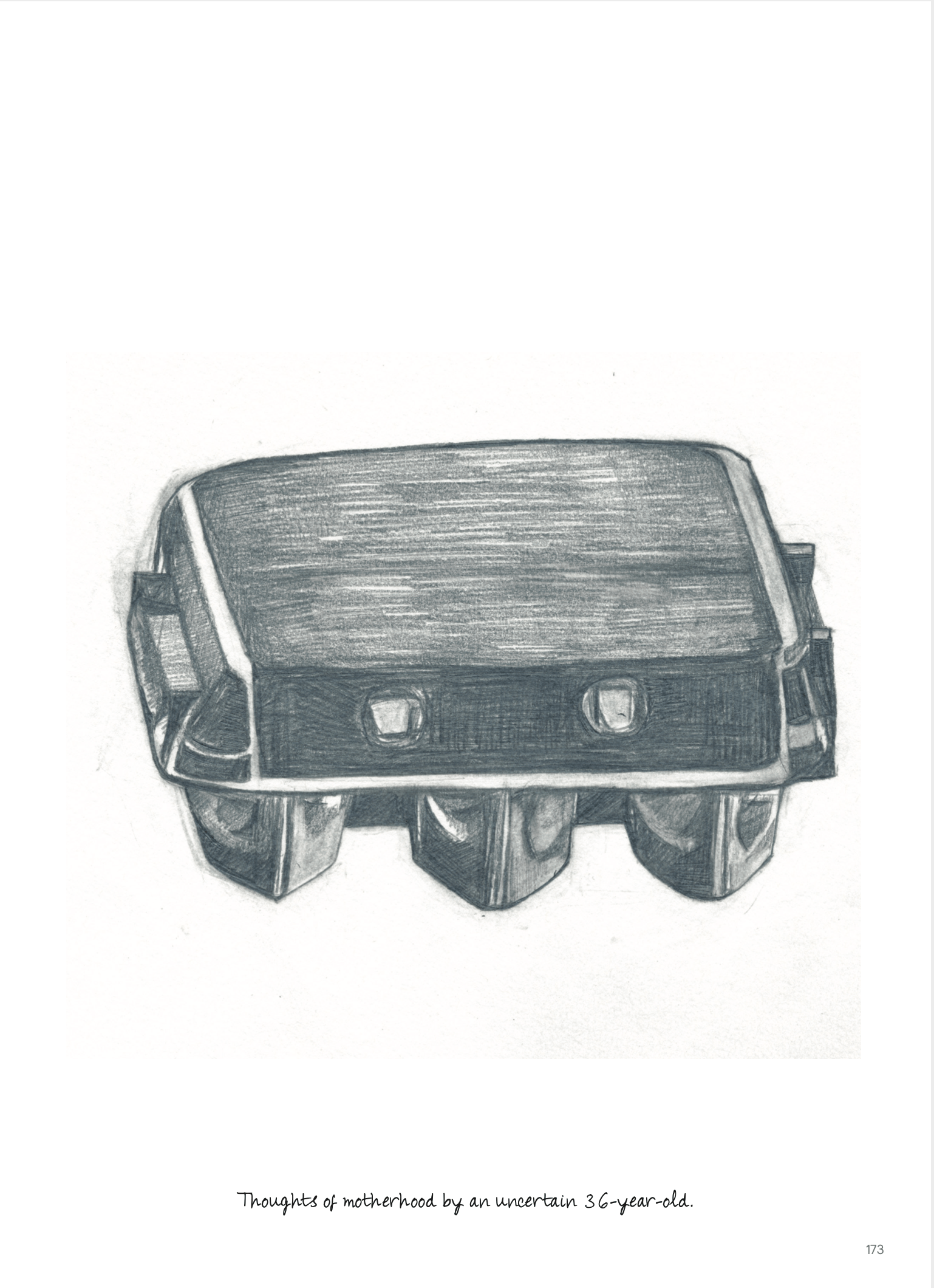

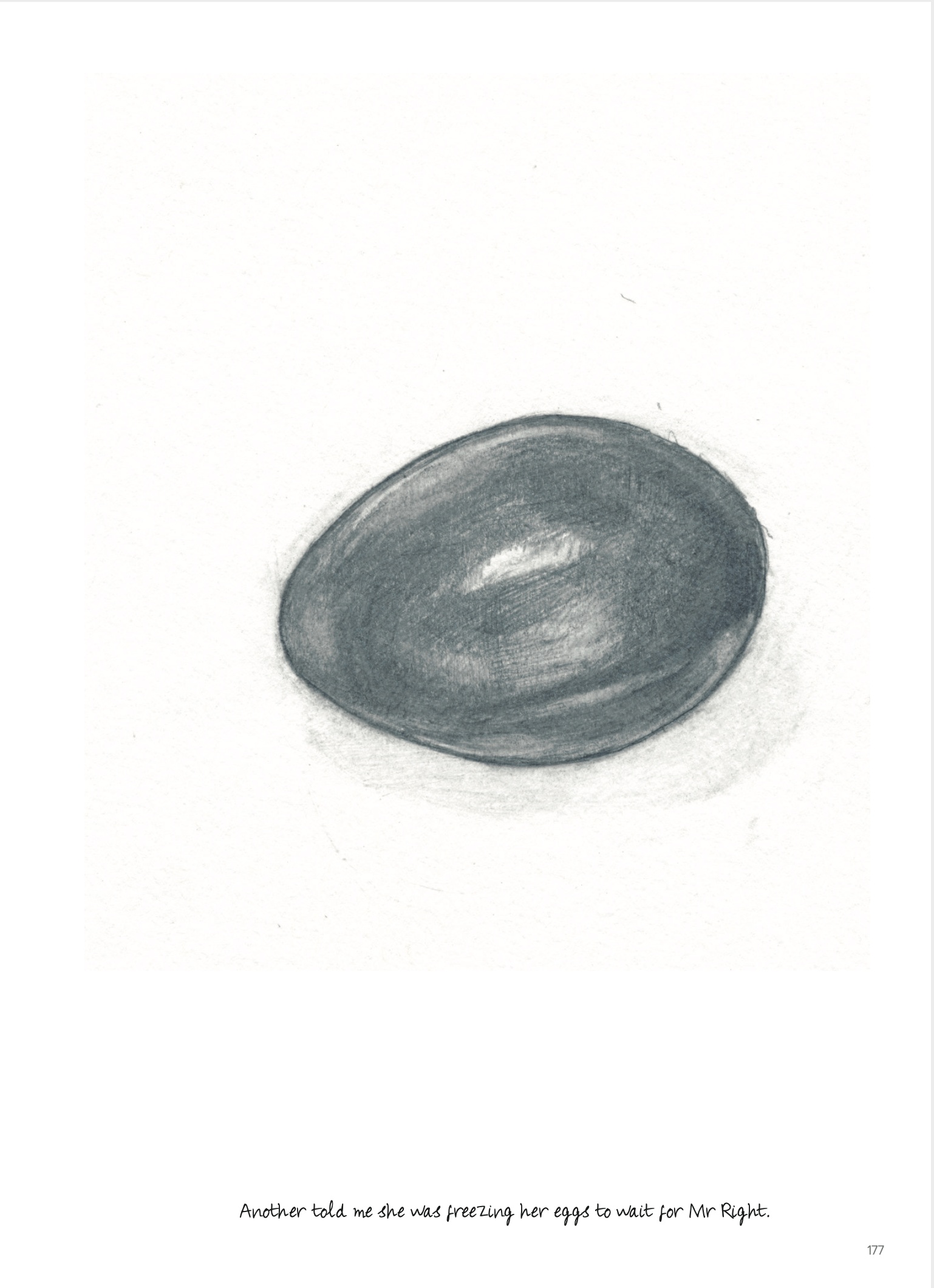

The most striking sequence of images, however, is found on pages 173 through 181. A carton of eggs is drawn in various stages of opening, closing, sometimes with four eggs, other times with three, and often with the eggs outside of the carton. The egg sequence finishes on an open carton of six eggs. It is Lightman’s reflection on fertility, age, pressure from family and friends, and her own needs and desires regarding pregnancy and motherhood. This sequence is beautifully executed and impactful. The book ends with the arrival of Lightman’s son and her reflections on motherhood.

There are moments of great joy intermingled with sadness throughout the book, but overall, the book is sombre, even morose in tone. There is very little light or laughter throughout the pages, though that is not a criticism (merely an observation); rather, the emotionality of the everyday object set against a textual rendering of Lightman’s feelings reminds the reader of how our own lives and emotions are closely connected to even the most mundane objects around us: a tube of moisturiser, an empty baking tin, or a street sign. All are material objects which can embody memory and sense. The stilting narrative encourages the reader to make connections between Lightman’s words and those drawn images even when there is maybe no sense of reason nor rhyme to them. For this reason, Lightman’s book is not a comic book or a graphic novel in the conventional sense, but this is welcome since it is time, we moved past such limited definitions of what comic books are.

As noted, the major themes of the book centre on mental health, family, and fertility in particular. Such themes are prevalent also throughout the biblical narrative of the matriarch Sarah in Genesis, though Lightman does not often directly reference that character (notable exceptions are pages 13, 15, and 231). Instead, the connection is subliminal; the reader who knows the biblical Sarah’s story can see reflections of it woven throughout Lightman’s chronicle and may also delight in finding the resonances and echoes when they appear. Such shadows are heightened by Lightman’s discussions of her Jewish heritage and faith, which link the reader back not only to the Jewish text of the Bible but also to how those allusions continue to shape and be shaped by Lightman’s interactions with them.

This is not just a book about Lightman’s life. Nor is it a book just about Jewish identity, or feminism, or mental health, or fertility and parenthood. It is a book about how the stories about our past inevitably influence the potential of our future. The ruminations on Lightman’s Jewish identity, her quest to become a mother, her relationships, her family, and her visual storytelling through objects is a reminder that, like the biblical Sarah, the journeys we take in our lives are often entirely out of our control, but what we can control is our response and maybe, sometimes, for a little while at least, our direction of travel.

The Book of Sarah by Sarah Lightman is published by Myriad Edition priced £19.99.

This review was previously published in Literature and Belief 40.2 & 41:1 (2020 & 2021) in a special issue devoted to Jewish Graphic Novels, edited by Victoria Aarons. Thank you to the Centre for the Study of Christian Values in Literature at Brigham Young University and the author for allowing us to republish it in an edited form.